Last week I met a dear friend for lunch. She is in her late eighties and lately she has struggled with health issues, including a few falls, the latest causing a broken wrist – a particular handicap for her as she is a writer. She repeatedly tells us that growing old is no fun, yet she is full of life, a tonic when you meet her. She is an attentive observer of the human condition, has a feisty spirit and wry sense of humour. She is also a woman of deep faith and, like the prophets, has the confidence to rail against God. The conversation began like this,

‘I am really angry with Jesus and I’m going to tell him so! We are always being told that that God became human in Jesus so that God could experience all that we humans experience. Well Jesus didn’t experience old age did he! How could he know what all this feels like when he died in his early thirties!’

The mini-rant over, we enjoyed wide-ranging and stimulating conversation, as always, but the encounter challenged me to reflect more deeply on how we reconcile within ourselves failing health, loss of loved ones, our own failures and fears and ultimately our own mortality. I think Lent offers us an invitation to go to ‘the place of the soul‘, as Celtic writers often put it, that place of within us where, at a gut level we know what is true and real and of God, that place within us where transformation can happen – if we are open to it.

How do we understand the invocation, ‘Repent and believe in the Gospel’ on Ash Wednesday? Could ‘repent’ this year, be an invitation to think differently, reset our inner compass, and perhaps commit to a few simple daily practices that might help bring about a ‘metanoia’ – that radical change of heart to which we are all called and for which we often long.

Our fundamental ‘sin’ – the failure to trust God’s unfailing and eternal love for us?

To begin with could we re-examine our image of God? Do we really believe that we are made in God’s image and are called to grow in likeness of God? Do we really trust that we are loved unconditionally and forever? Even with all our faults and failings, our sins and transgressions, our destructive patterns of behaviour, God only ever looks on us with love and compassion and only ever desires that we feel this love – deeply. Consider the image of the forgiving father Jesus gives us in the gospel, the father who is constantly on the look-out for the return of his prodigal son, whose love pours out in lavish celebration when the errant son finally arrives home. No judgement. No blame. No recrimination. Only open arms and rejoicing.

‘Come back to me, with all your heart, don’t let fear keep us apart’, wrote Dominican priest and musician Gregory Norbert, taking to heart the message of the prophet Hosea. The hymn chorus;

‘Long have I waited for

Your coming home to me

And living deeply our new lives’,

offers an opportunity for much reflection. Perhaps we have an image of God that needs to be redeemed? Can we repent of any notion of a God who is ever watchful, ready to judge and condemn and instead trust in the God of compassion and forgiveness revealed by Jesus?

The ultimate witness to God’s unconditional love is, of course, the cross. God became human in Jesus to show the extent of God’s love for us. The inevitable outcome of Jesus proclaiming and living God’s kingdom of love, justice and peace, without compromise or collusion with the ‘powers and principalities’ of his time, was death on the cross, the ultimate sacrifice of love, which, in time and even in our day other saints prophets have courageously followed. Can we use this Lent to turn around our thinking and perhaps consider sin more as of not trusting in that love for which Jesus gave his life? What are the fears that ‘keep us apart’ from ‘living more deeply’ in that love?

One simple practice could be to ask ourselves, ‘How can I love more deeply, trust more readily today? Can I affirm and bless another person today? Is there someone I need to forgive and am I ready?

The Cross of Light – ‘What we don’t transform we transmit’ – Richard Rohr

‘Two universal paths of transformation have been available to every human being God has created: great love and great suffering.’

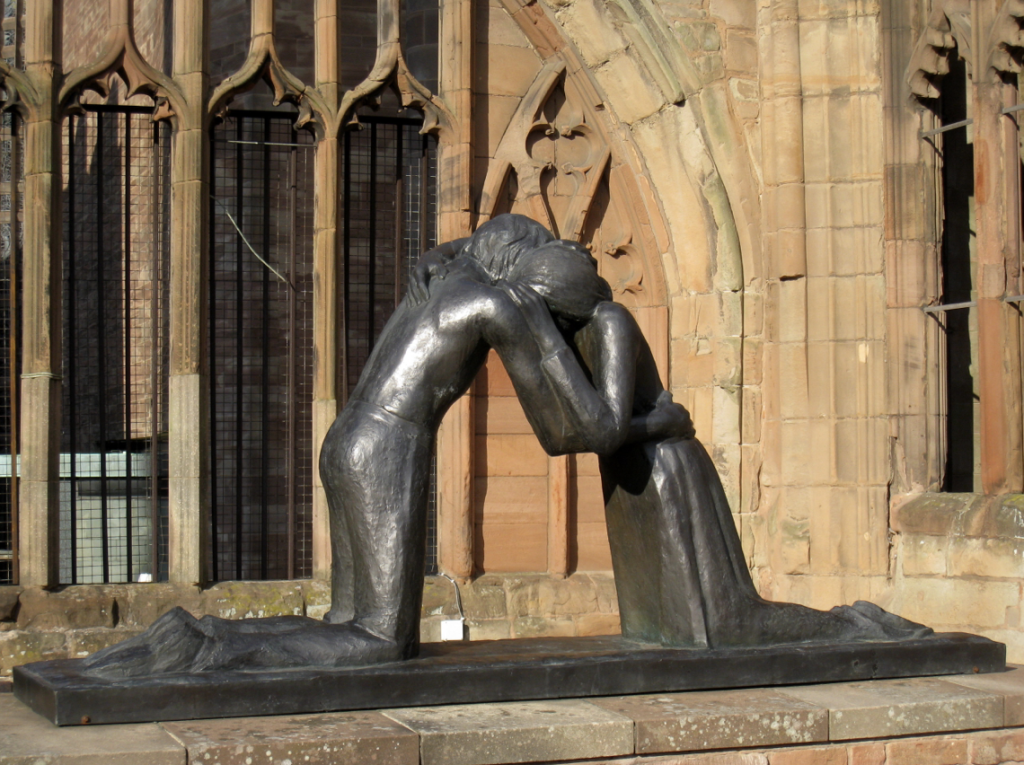

A more difficult challenge is to reflect on how we deal with our pain and loss, which is at the heart of the Christian story, says spiritual teacher Fr Richard Rohr. If we don’t let our pain be transformed within us, we will inevitably transmit it, he claims. Our parish has as a motif, ‘the Cross of Light’.

It symbolises that on Good Friday, at the point when Jesus trusted completely in his Father and gave up his life, the cross is shattered, death is overcome and the light of resurrection breaks through. Rohr is convinced that the only way we, too, can let go is if we trust that we are held safely and can fall back into the arms of one who loves us extravagantly, as Jesus did. Jesus offers us a way of enabling our pain to breakthrough, a pattern for our daily living. Rather than simply a case of ‘offering it up’, his total surrender breaks through, identifies and is in solidarity with the pain of others, the pain of the world. It is a radically different focus.

Let us pray, this Lent, that we can find that trust, the letting go, knowing we are always held. My dear luncheon friend seems able to live this way, which makes her a blessing for those around her.

May we give thanks for such people in our lives. May we, too, have the courage to understand what it takes to see with the lens of love.

Let us search with our whole soul for that which gives light and hope, healing and compassion.

May we always continue to believe in Spring, especially in the midst of our inevitable Winters.

Margaret Siberry

Leeds Justice and Peace Commission